In the Return of Martin Guerre, a man shows up in a small, French village claiming to be a soldier back from the war. He quickly moves into his old house and resumes his relationship with his former wife. But is he telling the truth? His feet don’t fit his old shoes at the cobblers’ shop. The man is an imposter.

Today, Martin Guerre’s story would be almost impossible. Impersonation is possible only online. In the physical world, humans are stopped everywhere, all of the time, and told to account for themselves to some machine or another. This happens in the airport, at the bus station, on the highway. It happens on the streets of many cities, which are filled with cameras, filming day and night. This constant surveillance has been a boon for safety in liberal democracies; less so in autocratic states. In the film Minority Report (based on the story of the same name by Philip K. Dick), Tom Cruise has surgery to remove his eyeballs to avoid retinal scans that would have given his location away to the police. It will not be long before such technologies become widespread.

But we don’t have to wait for retinal scans to feel the long arm of the security state. Everything from library cards to cell phone registration produces data points, nuggets of identifying information about each and every one of us. Almost everything the government needs to identify not only who you are, but most of the facts about your life, exists in a computer database somewhere. Many of these databases are searchable and connected to the internet. Those databases that aren’t under government control, but are privately owned, like your Google search history, can be accessed by the government for certain purposes.

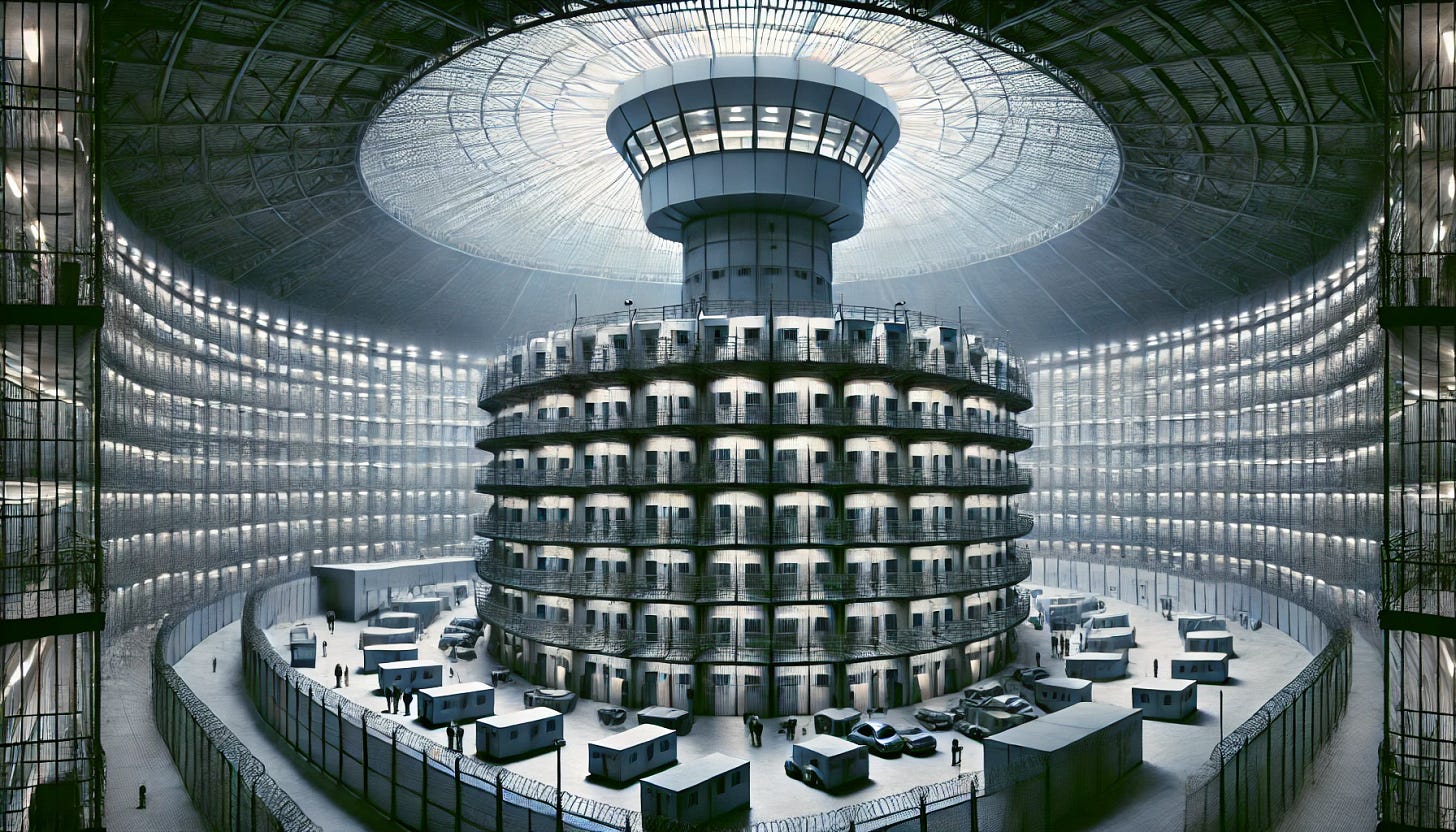

Meanwhile, the number of unregistered, or under-registered, human beings keeps shrinking, even in the poorest parts of the world. The World Bank and other international organizations are pushing the governments of poor countries to roll-out biometric registration through projects like ID4D and Get Everyone In the Picture. Such programs are billed as necessary to protect human rights. Unregistered people do not exist “on paper,” a place increasingly crucial to accessing rights and services. It’s true that ID is needed to access health care and education in most countries today. It’s also true that there is a dark side to all of this fingerprinting and retinal scanning. The world is poised on the edge of a panopticon of surveillance that was the stuff of science fiction only a decade ago, as AI shrinks the remaining undocumented parts of our lives to zero.

AI will allow governments to process the vast amounts of data they are collecting on each and every person on earth through the simple function of token prediction, where each data point is used to arrive at the most likely next data point. It’s not hard to imagine a future where AI can be quickly trained on your past actions to provide a model of what your future actions may be.

Imagine a future where you do not need to give your passport at the airport because not only were you identified as you entered the terminal, but the government’s travel ID system predicted you were planning a trip to Paris before you’d even booked your tickets. AI may even have assigned you a number based on the likelihood of you trying to break an immigration law. It will know your propensity to sneak bananas through customs and your hypochondriac insistence on travelling with a small pharmacy of medicines in your bag. Will the AI’s predictions of your travel behaviour be 100% accurate? They don’t need to be. All they need to be is better than 50% and they will be helpful to border security guards. This is the future, and it is scary.

For migrants and refugees, the panopticon will be devastating. The clandestine movements and negotiations that allow people to escape persecution and disaster will end. Only authorized humanitarian departures will be possible, and they, too, will be predicted and controlled by AI. As Mario Pasquale Amoroso points out, the robot who “interviews” you for asylum will judge, based on your entire life history and millions of other data points about you, whether or not you have a “credible fear” of being returned to your country. Again, the robot asylum officer doesn’t need to be 100% accurate, it just need to outperform humans, or convince the government that its outperforming them, since “credible fear” interviews are subjective. For stateless people, this brave new world will be catastrophic. Gone will be the grey economy and fake documents that allows stateless people to scrape by in a world designed only for citizens. They will be simultaneously completely invisible and totally exposed.

In some ways, the most disturbing part of this future will be the introduction into our lives of robots that seem human and take over human functions in migration control and border policing, introducing competency and efficiency into what should be a messy and human process. Already, the process of migration and immigration is dehumanizing. Family separations under the first Trump administration happened because the Trump administration started strictly enforcing US immigration laws as they were written on the books.

Will robot asylum officers bring more empathy because they can’t get tired or develop compassion fatigue? Will they be capable of the flexibility that is the lifeblood of the global migration system, the ability to sometimes bend the rules to produce a just outcome? AI is ruled by 1s and 0s, and computers excel at logic and efficiency. These are some of the attributes we need least when it comes to migration. Like all systems, the global system of borders and visas works best in its inefficiencies, its gaps and spaces. We will miss these gaps and spaces when they’re gone.